Hope in early medieval canon law

While the dark clouds of uninformed, misguided higher education policy are gathering over universities in the Netherlands, I was asked to talk about hope in early medieval canon law for the International Medieval Conference (IMC) at Leeds this year. The confusion did not end there: canon law—with its flurry of prohibitions, penance, and anathemas—does not strike one as a textual genre in which hope is a central feature. Yet, there is more than meets the eye. In fact, I should like to argue in the course of this paper that canon law is the literary genre of hope par excellence.

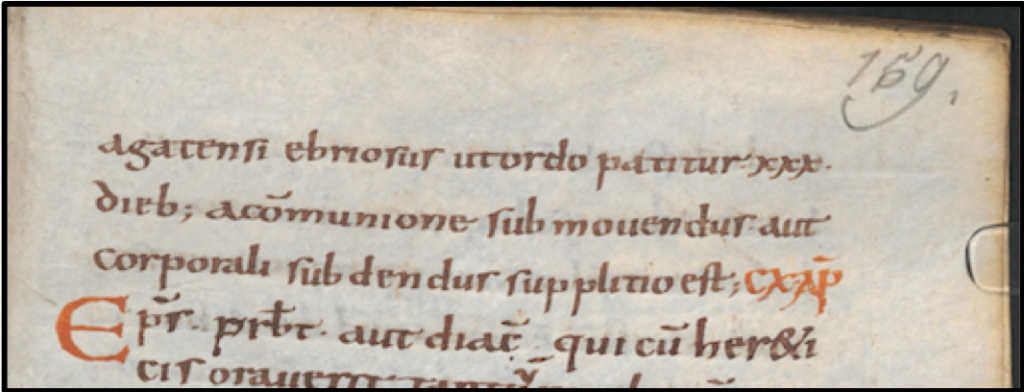

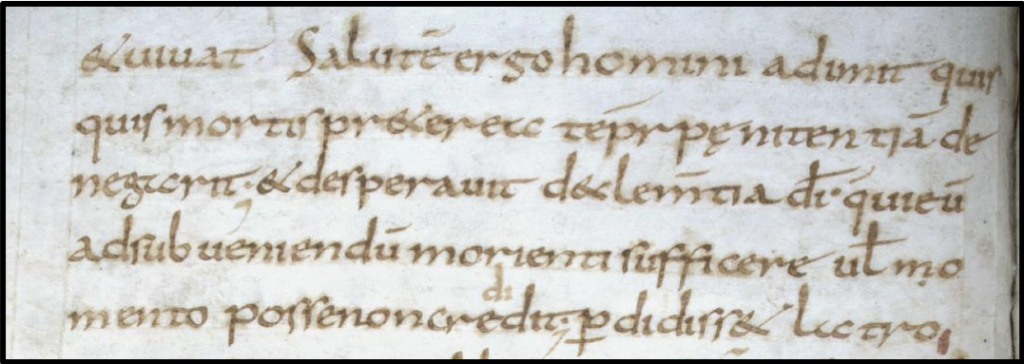

Collection in 400 chapters, c. 109

Vienna, ÖNB lat. 522, f. 159r

In a way, this statement is perhaps a tautology: in many respects, the act of writing, of producing something for future readers is always a testimony of hope. In an early call to human scientists to put emotions front and centre in their studies, Thomas Meisenhelder in 1982 defined hope as a particularly active emotion; one ‘which includes the sure recognition of the future’s uncertainty’, but still ‘continues to actively confront the future as if one’s actions had effective meaning’. Hope can then be contrasted with the passive endurance of an unalterable future. In a particularly moving description, Meisenhelder describes the hopeless person as one who ‘accepts the inevitability of his or her singular life and lonely death’. In contrast, the hopeful denies one’s finite aloneness and actively confront the two basic facts of life: loneliness and death.1

Viewed as such, the activity of writing down religious and ecclesiastical rules is a prominently hopeful act. The aim of the compilers was, one assumes, to cleanse society—and future societies—of disruptive behaviour and to help people alter their lives to accord better with an ideal, Christian future. This would be a particularly ‘big hope’, in the scheme proposed by Peter Burke, in a recent article titled ‘Does Hope Have a History?’ (the answer is, thankfully, ‘yes’). He distinguished the various objects of hope in ‘big hopes’ on the one hand (hopes for a better world, for the entire human race) and ‘small hopes’ (individual hopes, everyday hopes).2

The prefaces to canonical collections, one could argue, communicate the ‘smaller hopes’ of the compilers, i.e. the aims which they hope their specific collection serves to accomplish, but also refer to that ‘bigger hope’, the one concerning humankind. Dionysius Exiguus, the compiler of the Dionysiana, is clear about the end goal of canonical law in general, when he observes that the ‘discipline of ecclesiastical order, remaining invulnerable, might offer to all Christians a gateway for gaining the eternal prize.’ The latter Collectio Sanblasiana adopts the same preface.

On the face of it, many ecclesiastical and religious rules appear to have no patience for the emotion or mood of hope. Especially penitentials have a tendency to state what one cannot do and swiftly provide the satisfaction that will lead to absolution. To quote an example from the Penitential of Theodore:

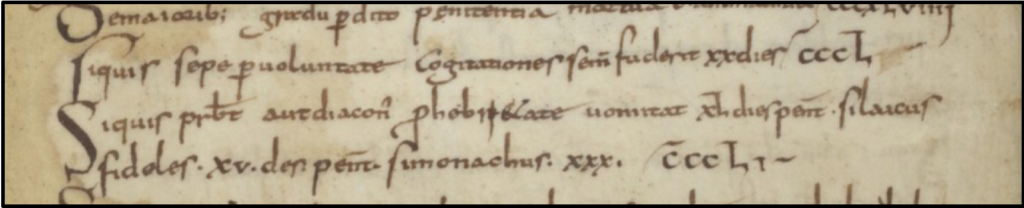

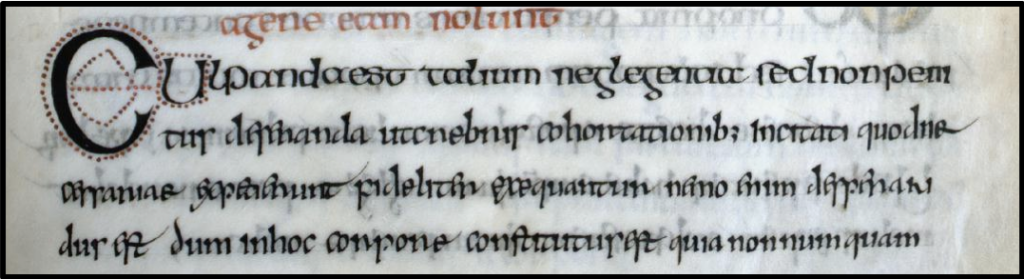

Collection in 400 chapters, c. 350

Paris, BnF lat. 2316, fol. 115v

These rules have both hope and fear built-in to them: there is the fear that one may die during the process of penance, which would result in the sinner going to the afterlife without have paid off all of his sins yet. But there is also the hope that, after this not-impossible series of penitential acts, one can be readmitted within the fold of the Christian community.

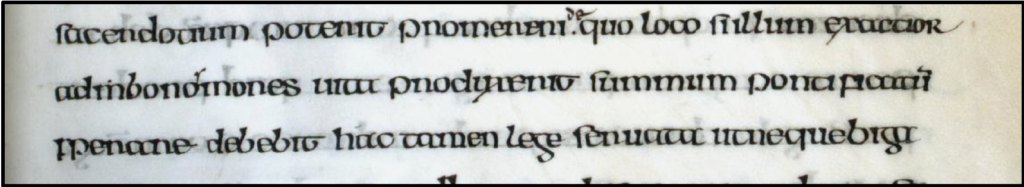

The words for hope, spes and sperare, in fact occur sparsely within the canonical collections and on first glance. And when they do occur, it often seems as a particular idiomatic expression, a way of phrasing whose particular choice of words is of secondary importance. One example is found in the letter of Pope Zosimus to Bishop Hesychius on clerical advancement, which is quoted in the chronologically arranged Sanblasiana as well as the systematic Herovalliana. In it the pope prescribes a step-by-step advancements of clerics rather than a rapid promotion of, potentially unfit, men. If a mature priest, having risen through the ranks, is seen to be leading a good moral life, Zosimus writes, he must hope for the ‘highest pontificate’.

Cologne, Dombibliothek 213, fol. 104r

The word hope is used in the same context of clerical ranks and positions in threecanons from the council of Antioch (AD 341). The subject here are offending clerics who persist in their errors. Canon 3 discusses the priest of deacon who has forsaken his own parish and disobeys his bishop’s summons to return. He is to be deposed ‘with no hope for his restoration’. Similarly, deposed bishops, priests or deacons who nevertheless continue to perform part of their ministry, shall no longer have any hope for restoration in another synod (canon 4). Again, focusing on deposed clergy, canon 12 notes that these clerics need to appeal to higher authorities but not trouble the emperor with their predicament. If they do, they will have no ‘hope for future restitution’.

Pope Leo’s letter to Bishop Ianuarius of Aquilaea also addresses the issue of clergy who have previously erred with the heretics and schismatics. They need to make amends and condemn the teachings when returning to the church and should ‘consider it a great indulgence, if they be allowed to remain undisturbed in their present rank without any hope of further advancement’)

The emotion of hope is clearly used here to refer to a better future, in which the happy position of the person involved is restored or even advanced. The expression of having ‘no hope’ has a distinct ring of finality: while none of these deposed clerics who do repent, are described as having any right to expect future restorations, the offenses described are such that for non-repentant clergy the avenue possible rehabilitation is permanently closed off. Still having hope, gives no guarantees; having no hope guarantees the subjects’ miserable state.

Hope towards God

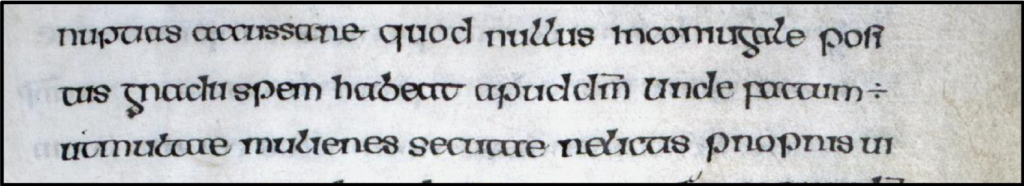

The concept of having no hope probably invoked some strong emotional responses. The phrase spes apud Deum occurs three times in the text of the fourth-century synod of Gangra, which was contemporary with the council of Antioch. The word hope features twice in the council’s prefatory letter addressed to the clergy of Armenia, and once in its second canon. The phrase is used to signify those who have hope for salvation by God. The council condemns the teachings of Bishop Eustathius of Sebaste, who in his promotion of an ascetic monasticism apparently taught that ‘no one living in a state of marriage has any hope towards god’.

Gangra (4th c.), praefatio in Sanblasiana

Cologne, Dombibliothek 213, fol. 28r

The council claimed that because of these teachings many women had left their lawful husbands and the other way around, with many subsequently ‘not being able to contain’ and falling into adultery. Eustathius followers, fulminating against many of the church’s customs, held some extreme ascetic views; they condemned those wealthy faithful who did not alienate from all their possessions as having nothing to hope from God. Similarly, the eating of meat was denounced; those who did eat meat, even when it was otherwise not tainted, had ‘no hope’.

‘Those who hope’ is thus shorthand for orthodox, devout Christians. It is apparently felt particularly hurtful that the ascetic zealots following Eustathius claimed that Christians, whom the council finds no fault with, are described as having no hope; the description denies their piety and strips them of their Christianity. The finality of such a branding, as the use of the phrase by the council of Antioch suggests, adds to the emotional distress of the council members.

This use of the concept of hope and hopelessness is clear in some other canons. For instance, a canon from the sixth-century synod of Epaone in Burgundy, which is incorporated in the Collectio Herovalliana, allowed ‘despaired and dying heretics’ (desperatis et decumbentibus haereticis), desiring for immediate conversion, to be rescued by a priest using unction. ‘Despaired heretics’ may be a tautology: obviously, heretics in this scheme would have no hope. The compiler of the Herovalliana notes that the penitents cannot receive unction; quoting a sentence from Pope Innocent’s letter, since the unction is a sacrament—just like communion—from which penitents are barred.

A reminiscent situation is detailed in the letter of Pope Celestine to the bishops of Narbonne and Vienne, a staple of early medieval canonical collections. It touches on an essential element of the salvation, that is the fact priests may not deny sinners the possibility of penance. It reads: ‘He thus withdraws the salvation from the man whoever denies [a gloss has here: the hoped-for] penance at the time of death.’ Intriguingly, it is the priest who actively denies the penance to a dying man/woman who is condemned and must fear for his soul: ‘and he despaired for the clemency of God, who appointed him to rescue the dying, but [at the moment] was not able to believe.’.

Cologne, Dombibliothek 122, fols. 16r-v

The emotion of hope, the promise of hope, is thus intimately connected with the promise of eternal life that belongs to all devout Christians. Having no hope is the equivalent of not being a devout Christian, and being denied that promise.

Now, none of these pronouncements of hopelessness have the character of punishment; these are simply statements of fact. Some offenses to God will make it practically impossible to be granted salvation by God, and canon law will explain this to the reader. For other offenses, there is the option of penitence. A penitent, as Leo explains, is not a hopeless person. In his letter to Rusticus, he discusses those who in sickness accept terms of penitence, and when they have recovered, refuse to keep them. He pronounces that

‘such men’s neglect is to be blamed but not finally to be abandoned, in order that they may be incited by frequent exhortations to carry out faithfully what under stress of need they asked for. For no one is to be despaired of so long as he remains in this body, because sometimes what the diffidence of age puts off is accomplished by maturer counsels’

Cologne, Dombibliothek 213, fols. 126r

Punishments—despite the word being used in literature—, and this is particularly important, are generally not meted out in canon law. It does not adhere in any way to the utilitarian and retributive philosophies of punishment. The penalties for offenses against God or his Church, are inescapable and will be dispensed after death. As Leo states in his letter to Ianuarius: ‘No slight penalty does he incur from the Lord…’ (non levem apud dominum noxam incurrit). Canon law dispenses knowledge, rather than punishment; it offers guidelines which help Christians to not commit mortal transgressions, by formulating which of these offenses result in despair. Systematically arranged collections, incorporating material from penitential handbooks, do even more: they offer remedies in the form of penance.

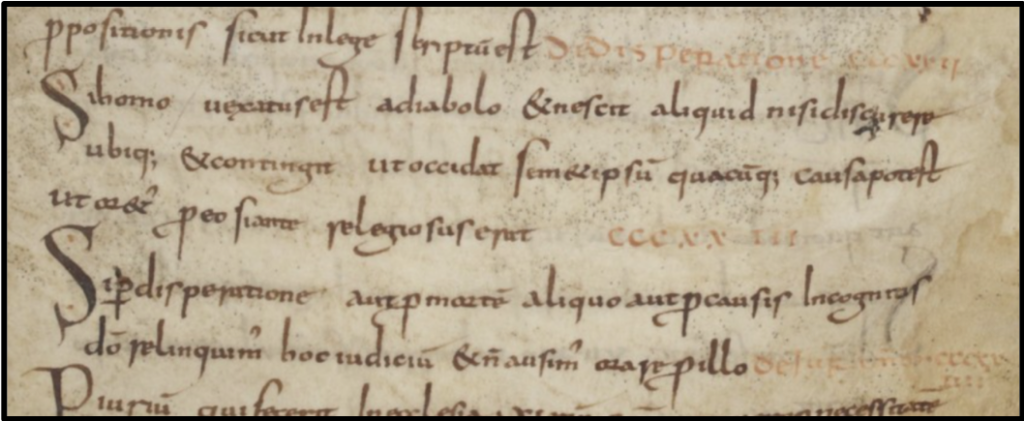

Read this way, hopelessness and despair gain a different quality than the literal translation to modern concepts would produce. This is apparent in two chapters (322-3) in the Collection in 400 chapters, which are drawn from the Penitential of Theodore. The compiler of the Collection in 400 chapters, actually included a chapter ‘on desperation’ (De disperatione).

Paris, BnF lat. 2316, fol. 114r

Concerning despair: If a man is moved by the devil and he knows nothing but to wander everywhere and it happens that he kills himself, whatever the cause may be, let one pray for him, if he earlier was a religious man.

If out of despair or some fear or an unknown reason, we leave this judgement to God and we are not prepared to pray for him.

Collectio 400 capitulorum, cc. 322-323

A similar, more heart-warming sentiment is expressed somewhat later in the same collection, again taken from Theodore.

Paris, BnF lat. 2316, fol. 114r

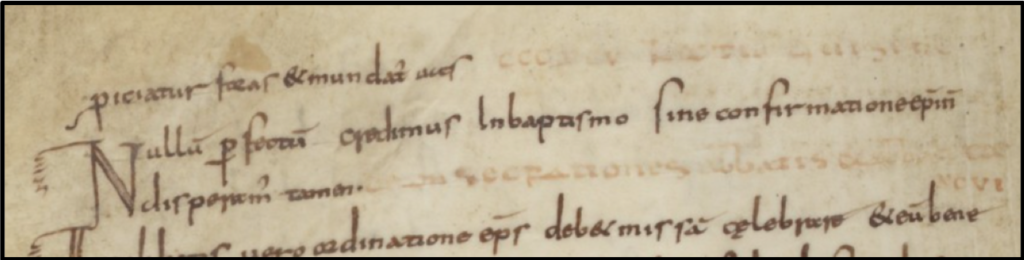

We believe no one to be complete in baptism without the confirmation of the bishop, yet we do not despair.

Collectio 400 capitulorum, c. 395

That is to say, there is still hope for those baptised without episcopal confirmation.

Concluding

This brief overview of the ways in which hope is present in canonical collections of the early Middle Ages produces specifically the emotion of hope, rather than the virtue as described by Augustine. In this, it accords well with the sentiment expressed in Hebrews 7:18-19: ‘There is indeed a setting aside of the former commandment, because of the weakness and unprofitableness thereof: (For the law brought nothing to perfection,) but a bringing in of a better hope, by which we draw nigh to God.’ With the provision of remedies and healing penance, the canonical collections truly are works of hope par excellence.