I always expected that my book on the Irish scholarly presence at the monastery of St. Gall would elicit critical responses. This is not to say that I do not prefer compliments and positive appraisals, but I am fully aware that my analysis of the spread of Hiberno-Latin scholarship on the Continent ruffles the feathers of those colleagues who would rather emphasise the Irish element of the intellectual achievements by Irishmen. Those on the nativist side of the spectrum can be troubled by my assessment that not all that glitters is (completely) green and that we can learn more about early medieval intellectual history when we include all possible factors that promoted and shaped Irish learning, and curb our modern impulses to classify everything along national(ist) and ethnic lines.

Professor Ó Cróinín’s review in the Journal of British Studies is the first review of my book I have read so far1 and it is decidedly negative. In the conviction that a (negative) review need not be the end of the academic conversation, but rather a continuation, I gladly take this opportunity to respond to some parts of his short review. For while I do not expect to convince Professor Ó Cróinín of all of my conclusions, I do think it is important to point out where the review does its readers a disservice by misrepresenting my argument. And unfortunately it does so repeatedly and consistently.

It is probably good to briefly describe my approach to the evidence in the book: since the tremendous contribution of Irish scholarship to European culture is not in doubt and the Irish intellectual presence at St. Gall is undisputed (see below), it is possible and instructive to study the circumstance in which Irish scholarship gained such a position of influence, in particular the routes taken over the Continent and the reception it got in St. Gall. To quote the introduction (p. 2):

‘I am interested in the place of Irish scholarship at this Alpine monastery: how was it received, read and valued and what part did its Irish origin play in all this?’

My approach tests two assumptions often expounded, implicitly and explicitly, in earlier scholarship: 1) that St. Gall acted as a bridgehead (or gateway) of Irish scholarship, meaning that it was at St. Gall that Irish texts made landfall and that this monastic centre had a ‘special relationship’ with Ireland, and 2) that the scribes and masters at St. Gall were always aware of the Irish heritage of the material before them, or that they (always) appreciated it because of its Irish credentials. In both cases, my findings qualify these assumptions: I found that much of the Irish material came to St. Gall via other continental centres, rather than directly from Ireland, and was graciously received by St. Gall scholars but often without being aware of (or particularly interested in) its Irish background. As I stated in the conclusion, this thereby only underscores the value accorded to the Irish works for their practical use or intellectual quality. This point seems to have been lost on Ó Cróinín.

Ó Cróinín opens his argument by stating that I ‘set out to minimize’ the Irish influence at St. Gall a) ‘by questioning the significance of all the surviving Irish material in the abbey library’ and b) ‘by turning on their heads all the well-known references by continental writers to the Irish and their influence, and rather than seeing them as complimentary and admiring of Irish scholarship, viewing them instead as manifestations of anti-Irish animosity’. The use of the phrase ‘set out’ suggests intent (as does his search for my “motivation” some paragraphs down): Ó Cróinín suggests that I came to this subject in bad faith, with a not-so-hidden agenda to do damage to the reputation of eighth- and ninth-century Irishmen. Without offering any evidence for such malicious intent, Ó Cróinín thereby disqualifies the book from the outset. Perhaps it is illustrative to quote again from the introduction of the book (p. 2):

‘The early medieval Irish feats of scholarship were formidable. The labours of Irish thinkers, scribes and artists, in the form of original writings, preserved antique scholarship and works of art had lasting effects on European culture. The impressive breadth and depth of Irish scholarship in this period is undoubted and uncontested. If there was a civilization to be saved, the Irish certainly played a part in the rescue operation.’

I am interested to learn how this paragraph testifies to the intent to minimize Irish influence. I do not see it.

To me, but I expect also to other readers of the review, it would have been instructive to learn how, in Ó Cróinín’s eyes, I misinterpreted early medieval evidence, leading me to paint an erroneous picture. Ó Cróinín does not offer us any such observations. Instead, he repeats his original claim a number of times, stating how my book tries ‘to conjure’ evidence ‘out of existence’ (see below), engages in ‘relentless denigration’ and displays a ‘steady drumbeat of anti-Irish bias’. This seems to be exactly the function of that first sentence: to disqualify the book without need to analyse its contents.

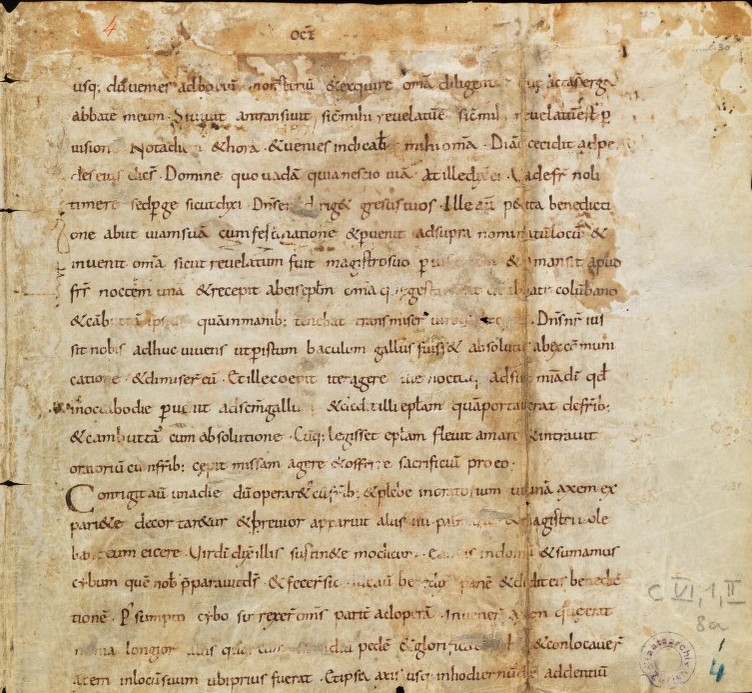

Actually, there is one supposed misreading on my part to which Ó Cróinín directs attention, namely my remark that the surviving sections of the Vita S. Galli uetustissima ‘make no reference to Ireland or to Irishmen’ (p. 19). I honestly do not know what Ó Cróinín is aiming at here. The full sentence from which he quotes a fragment is: ‘The surviving sections make no reference to Ireland or to Irishmen and we find no instance of geographically identifying words such as hibernia, scotigena or even scot(t)us in the entire text.’ This sentence comes at the end of a paragraph which explains how only fragments of this the oldest known Life of Gallus —now wonderfully published by the abbey press—survive on two mutilated ninth-century bifolia and how the missing parts probably include a large chunk of what would have been the opening of the text, where one would expect an exposé of Gallus’s origin and his travels with Columbanus (at least, that is what we find in the same place in the two Carolingian recastings of the Life). Due to the fragmentary nature of the extant life, we can never know the exact content or tone of the original opening of the uetustissima. I fail to see the factual error in this statement.

The ensuing observations in Ó Cróinín’s review are even more puzzling and no longer point to supposed factual errors or false interpretations. Instead, on the subject of the fascinating list of books written in Irish script—Libri Scottice scripti—, he comments that ‘not even Meeder’s reductionist approach can conjure this list out of existence—though that is not to say that he does not try.’ I am at a loss here: how do I try to negate the existence of this list, when I write ‘this list of books is an important, but complicated, witness to the relations between Ireland and St. Gall’ (p. 55)? Surely, I am not the first to address to the complications of this list, asking questions such as: why were the titles on the list not present in the catalogue proper? Could these books have included volumes in Anglo-Saxon script? In fact, Johannes Duft is much more blunt in his assessment of the books listed as ‘out-of-date’, ‘mostly unreadable’, ‘with no practical and direct importance’ to the St. Gall monks, and possibly including Anglo-Saxon books.2 It makes one wonder: would Ó Cróinín suggest that Johannes Duft—the eminent erstwhile St. Gall librarian-—set out to minimize the Irish contribution to St-Gall?

Equally puzzling is Ó Cróinín complaint that ‘while Meeder does write about the famous mid-ninth-century Irish scholars Marcus and his nephew Móengal (Marcellus), […] their influence, too, is minimized as much as possible, by subsuming it into a discussion of other (occasionally fictional) Irish visitors’. This seems a case of damned if you do, damned if you don’t: I covered all the evidence of Marcus and Móengal’s presence at St. Gall and, at one point, remark that ‘the contribution of the Irish Marcus and Marcellus to St. Gall’s intellectual networks […] was greater than the simple conveyance of books’. Such qualifications seem at odds with a book that is ‘relentlessly denigrating’ Irish scholarly influence. Furthermore, I would never conclude from the (sometimes sparse) evidence of Irish visitors to St. Gall that some of them were therefore ‘fictional’ (I have no reason to believe they are); perhaps Ó Cróinín could explain why he ‘conjures’ these men ‘out of existence’?

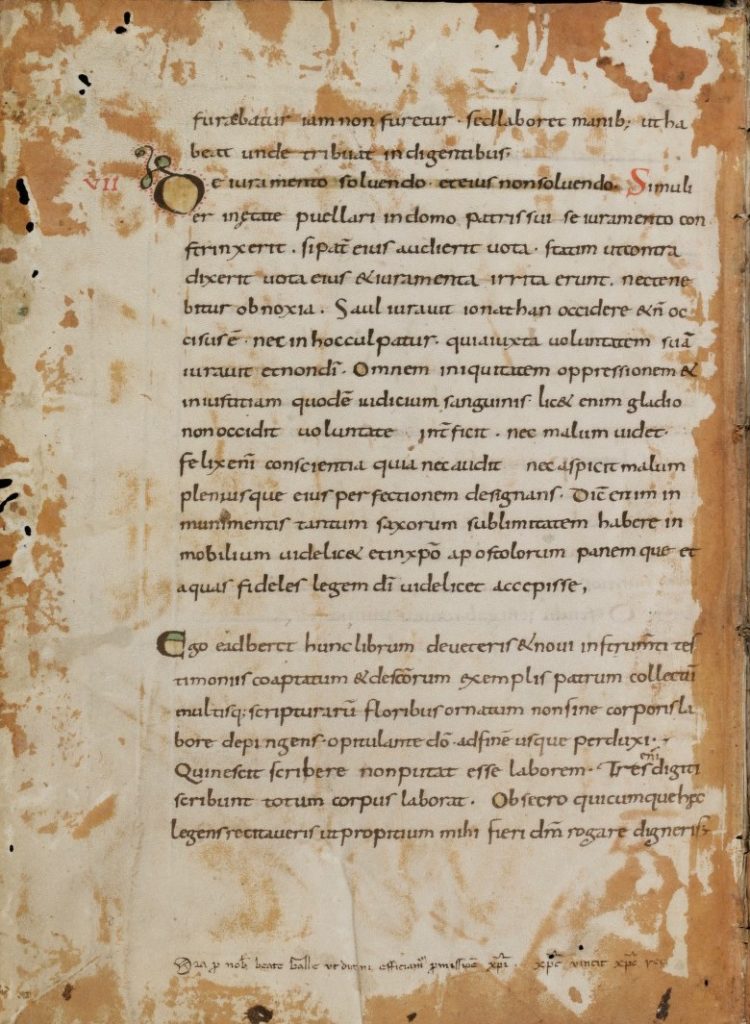

Ó Cróinín then seeks to determine the ‘motivation’ for ‘all this relentless denigration’. The following sentences are a little muddled, but seem to intimate that the denigration of Irish achievements stands in service to the elevation of Anglo-Saxon influence. As a case in point, Ó Cróinín offers my discussion on the mysterious Eadberct who is mentioned in the St. Gall copy of the Collectio canonum Hibernensis, which seems to have been referred to in the library catalogue as Collectio Eadberti de diuersis opusculis sanctorum patrum. It raises the question: if the St. Gall monks refer to the Hibernensis as ‘Eadberct’s collection’, what did they imagine his role to have been? Judging by the catalogue entry, they seemed to think he was more than (just) the copyist. Or, citing my concluding remark:

‘I do not intend to argue here for [Eadberct’s] authorship of the entire Hibernensis–the evidence for an Irish origin is simply overwhelming–but my point is that it is feasible to imagine the recipients of the Hibernensis at St. Gall assuming that Eadberct had a hand in the compilation of the collection.’

But this nuance, again, seems lost on Ó Cróinín.

http://www.e-codices.ch/en/csg/0243/254/0/Sequence-427

This is not to say that I do not welcome critical reviews of my book. Following its publication, I have found a number of unfortunate imperfections and mistakes (sometimes pointed out to me by colleagues, for which I am quite grateful). The paragraph on the ordo Romanus in MS 349 (p. 62), for instance, appears to stretch the argument, and my identification of the Old Testament king Roboam as Jeroboam is mistaken: it should be Solomon’s foolish son Rehoboam (p. 70-71). And finally, my metaphor of St. Gall as a ‘sink strainer’ is poorly chosen and I understand how Ó Cróinín (and others) might take offence: I regret that word choice and would probably now opt for another metaphor (perhaps “fish weir” would work?). The sentence following the offending word, however, makes my position clear:

‘With the streams of scholarship rushing through St. Gall, an impressive number of Irish works were trapped by its monks. Partly thanks to the cupidity of the St. Gall monks, partly owing to its convenient location, and partly due to the fortuitous survival of so much of the library’s holding, we have this unique collection to study.’

The scholars and scribes of St. Gall actively sought to acquire and copy the scholarship that they found within their intellectual network: in their selection, the background (e.g. Irishness) of these texts took a backseat to practicality, intellectual value, and other concerns. The late ninth-century glosses in the breviary of St. Gall’s books (MS 728) testify to critical minds reflecting on the past indiscriminate acquisition policy of the monastery as a process of hit-and-miss. We can only be thankful to those earlier monks who were so eager to copy the scholarship that came within their reach.

I have not missed the subtle praise at the end of the review for almost the entire second half of the book as an ‘otherwise useful discussion of the St. Gall transmission of the important Irish texts De XII abusiuis saeculi (65–82) and the Hibernensis (83–98), as well as the St. Gall copies of the various penitentials, Irish and non-Irish (99–108).’ I appreciate these words. But I cannot pretend Ó Cróinín’s review is not a little frustrating. Here’s the thing: personally, I am in constant awe of the achievements of the Irish scholars of the early Middle Ages and convinced of their formidable influence on European culture. But my appreciation was not the topic of my study; the book focuses on how the monks of St. Gall appreciated Irish scholarship and how the Irishness impacted on its distribution and reception. It is frustrating that this central element did not get across to a valued and admired colleague like Prof. Ó Cróinín.

It is the duty of the author of a book to write precise, clearly and well-argued and I welcome any criticism that may help improve my future work. In my view, the onus is on the reviewer to read carefully. In this case, I think there is some room for improvement on that score.

April saw the publication of my book on the

April saw the publication of my book on the